Exploring Racial Politics, Personal History and Critical Reception: Clarence Brown’s Intruder in the Dust (1949)

Gwenda Young

Introduction

In their Introduction to the collection The New Film History: Sources, Methods, Approaches, editors James Chapman, Mark Glancy and Sue Harper note the recent reframing of film history to accommodate a more inclusive approach that considers how “contextual factors—the mode of production, the economic and cultural strategies of the studios, the intervention of the censors” might serve to influence film content and, in turn, shape our understanding of the text (3). Such a methodology was deemed necessary after the excesses of the auteur studies of the 1960s and 1970s, but it perhaps risks overlooking the often-personal motives that might compel a director (or indeed an actor or producer) to take on a particular project. This article offers a case study of one film, Intruder in the Dust (Clarence Brown, 1949), tracing its place in the larger historical context of evolving attitudes to race in America from the early twentieth century to the aftermath of the Second World War, and examining the factors, both personal and societal, that influenced its content and reception. In doing so, I hope to bridge the gap between a more traditional auteur-based focus and a new film history approach that involves the examination of archival papers, oral sources and newly accessible contextual material (most notably, a range of critical reviews in both national and local press). [1]

Locating Intruder in the Dust

As one of the four big “race issue” films Hollywood produced in 1949, MGM’s film occupies a central place in the history of screen representations of blacks following the Second World War. Produced on the heels of independent film Lost Boundaries (Alfred Werker, 1949) and studio releases Home of the Brave (Mark Robson, 1949) and Pinky (Elia Kazan, 1949), Intruder in the Dust had perhaps the most impressive pedigree, adapted as it was from the novel by Pulitzer-prize-winning author William Faulkner. The soon-to-be blacklisted writer Ben Maddow provided the screenplay and Tennessee-raised Clarence Brown, a veteran of the studio system with a career stretching back to the 1910s, produced and directed it. When the film was released at the end of 1949, it garnered largely positive reviews, both in the general press and among film writers. In his review for the New York Times, Bosley Crowther praised Brown’s “brilliant, stirring” film that “slashes right down to the core of complex racial resentments and social divisions in the South” and “cosmically mocks the hollow pretense of ‘white supremacy’” (19). Edwin Schallert of the Los Angeles Times called it a “grimly courageous picture” (11), while the reviewer for the racially conservative The Chicago Daily Tribune noted it was “a blunt sketch of problems in race relations” that was both “probing” and “accurate” (“Mae Tinee” B7). Theorist and practitioner Paul Rotha, in a private letter to director Brown, commended the film for a “sincerity that we seldom see on the screen”; amateur filmmakers were advised to study the film for “effective examples of the dramatic uses of sound—and silence” (D.C. 1).

Many commentators praised the film’s “authenticity” and “realism”, the latter enhanced by the decision to film on location in Oxford, Mississippi and by the use of nonprofessionals in minor roles. Both studio publicity and critical reviews alluded to Brown’s Southern roots, suggesting that it was his “understanding” of Southern culture and collective mentality (implicitly, white) that ensured the film could play in both the North and the South without undue censorship or critical backlash. In a piece titled “No Phony Magnolias”, published in the Washington Post soon after the film’s release, Louisiana-born writer Hodding Carter voiced his admiration for how Faulkner’s complex exploration of racial tension and “the Southern character” had been sympathetically handled by the “Tennessee born and bred” Brown, pointing out that such nuanced representations had largely been absent from previous Hollywood films (B5). [2] Brown himself was keen to emphasise his insider’s knowledge—conveniently eliding the fact that he was actually born in the rather more Yankee state of Massachusetts—and in an interview with Philip Scheuer of the Los Angeles Times he enthused about working with the people of Faulkner’s hometown and confining his locations to “within a radius of three blocks, and at a bridge and cemetery 10 miles out” (D4). It was this feel for the local, the regional, that became for many critics one of the film’s chief merits and that earned it Faulkner’s seal of approval: when asked for his opinion, the usually reticent writer praised the film in customary terse style: “Mr. Brown knows his medium and he’s made a fine picture. I wish I had made it” (“A Surprise”17).

The credit given to Brown as the main instigator of the project was, on this occasion, entirely justified: it was on his suggestion (and persistent persuading) that MGM had bought the rights from Faulkner even before the novel had been published and such was his dedication to the project that he took on the dual roles of director and producer. Brown’s devotion to a novel that portrayed the complexities of racial history and interracial relations in the South—in typically opaque Faulkner style—may have struck many as surprising, especially given his career to date and his eschewal of political themes in his films. The career path Brown had carved out from 1920, when he graduated from a five-year apprenticeship with French director Maurice Tourneur, had seen him closely associated with both stars and the studio system. Since 1926 he had worked almost exclusively for MGM and developed a deep friendship with its head, Louis B. Mayer. [3] While Brown made a range of films in the next two decades, he was perhaps best known for his helming of star vehicles featuring A-listers such as Valentino, Garbo, Gable and Crawford. Yet, there was another side to Brown: scattered through decades of glittering movies that conscientiously reflected the MGM style of impossible glamour and escapism, were the smaller projects that he had initiated, such as Ah Wilderness! (1935); Of Human Hearts (1938); The Human Comedy (1943); and The Yearling (1946). In these forays into “Americana”, some of which predate his signing to MGM (e.g. two films he made for Universal, The Signal Tower (1924) and The Goose Woman (1925)), Brown displays a deep understanding of the lives of rural folk and a sensitivity towards landscape that aligns him with other American directors such as Henry King, King Vidor and John Ford, and indeed with writers such as Willa Cather and William Faulkner. Often shot on location and featuring a mix of professionals and nonprofessionals in key roles, it is these films that might just constitute Brown’s most significant and lasting work and that certainly offer the researcher a lineage within which his version of Intruder in the Dust might be placed. Despite this impressive pedigree, though, Intruder in the Dust was still a risky project for any director to take on and the stakes were especially high in a volatile postwar environment that was experiencing a radical questioning of racial issues and a widening schism between liberal and conservative ideologies. The fact that Brown was an arch-conservative, a man with close links to the anti-Communist Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals(he served as that organisation’s treasurer), made his decision to champion a race film all the more surprising. [4]

A closer examination of Brown’s life and of some of the historical events that shaped it, does, however, yield some possible explanations as to why he was so intent on adapting this difficult novel—one that had won little favour from Faulkner’s most ardent supporters—into a film. In interviews that he gave in his retirement, Brown cited Intruder in the Dust as his best film and the most significant one of his career. Even if his friend and boss Louis B. Mayer had threatened to “to throw me off the lot for just suggesting it”, he had persisted, winning over producer Dore Schary (the new pretender to the throne at MGM), who thought that it was about time that MGM made its own contribution to the current wave of race issue films (Carey 297). After all, in 1942 the trade publication Motion Picture Herald had declared that “Negro America is movie conscious” and Hollywood studios were waking up to the fact (“Negro” 33). While the liberal-minded Schary may have seen Intruder in the Dust as his chance to shake up his conservative employers and, in turn, perhaps capitalise on the new black dollar, Brown’s motivation was intensely personal, rooted in his familial identity and in a traumatic event of his adolescence. Although born in Massachusetts, Brown’s lineage was very much Southern: his father, Larkin, had strong connections to Georgia and had chosen to return to the South when he took up employment with Brookside Mills in Knoxville, Tennessee around 1903. [5] His only child, 13-year-old Clarence, thus spent his formative years in the South, moving between Knoxville and his paternal grandparents’ home in Atlanta. It was on one visit there, in September 1906, that he got caught up in events that would serve to irrevocably shape his complex attitude to race and, forty years later, motivate him to make Intruder in the Dust.

Bearing Witness: Brown and the Atlanta Race Riots (1906)

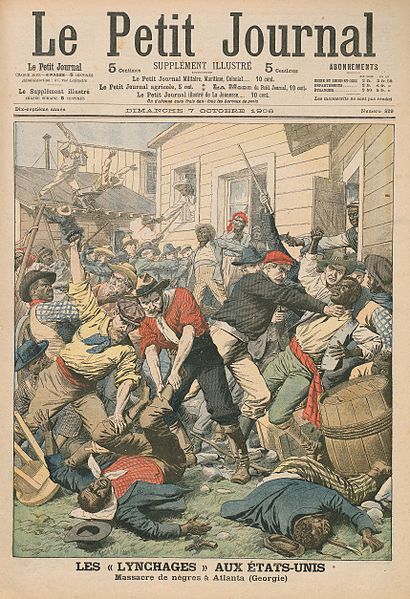

The Atlanta that Brown visited in the autumn of 1906 was a racially divided city, yet unquestionably more progressive than other Southern centres: although entirely politically disenfranchised, there was a substantial population of blacks that included a growing middle class and a wealthy elite, whose needs were served by thriving businesses and colleges. [6] However, even if blacks and whites generally coexisted more peaceably in Atlanta than in other Southern cities, there remained a significant undercurrent of racial tension and a growing resentment from some sections of the white populace toward the new black middle class. Historian Charles Crowe points to a negative campaign waged by a number of civic leaders and by newspapers such as the rabble-rousing Atlanta Evening News during the summer of 1906, that sought to stoke up white fears about miscegenation and that urged the police to take action to enforce segregation laws. Newspapers alleged that the white population was “in a state of siege”, confronted by a “torrid wave of black lust and fiendishness” that threatened “Caucasian virtue”; it was little wonder that all pretence of racial harmony had largely evaporated by the time Brown made his visit to the city (Crowe, “Racial Violence” 249). The simmering tensions built to a violent climax on the evening of 22 September when, following a day of police “clean ups” of black establishments, a crowd of 5000 people gathered in the downtown area (Crowe, “Racial Massacre” 156). In the hours that followed, Atlanta streets witnessed an extraordinary level of violence as an armed mob moved through the centre, smashing up black-owned homes and businesses, beating men, women and children, and murdering an estimated 25 blacks (168). Crowe, drawing on contemporary reports, notes the gruesome carnival-like atmosphere that pervaded:

The shocked but fascinated Arthur Hofman of Field’s minstrel show watched throngs of well dressed men, women and children on the sidewalks cheer and applaud mob activists beating Negroes in the streets. Frequently men left the sidewalks to join the rioters or returned from mob action to become spectators. To amuse the sidewalk galleries rioters would give a captured Negro a five yard start and then take up an armed chase with clubs and knives as the only policemen in sight energetically joined the assaults. (161)

Figure 1: Illustration from the French publication, Le Petit Journal. 7 Oct. 1906. The massacre was widely reported, both in the U.S. and Europe.

It was not just the astounding level of bloodthirstiness that horrified those who witnessed the mob in action but the fact that its members were made up of the expected “excitable boys” and well-dressed, middle class whites (Crowe, “Racial Massacre” 157–8). While it seems that most white people either participated or stood back to watch, there were a few who tried to stop the violence, motivated by a sense of humanity and, quite possibly, a peculiarly Southern attitude of paternal benevolence towards blacks. Crowe cites one example that is especially significant:

A Bijou Theater employee, named J. D. Belsa, reached his baggage men almost simultaneously with a murderous mob and daringly rushed them to safety behind locked doors. When the rioters tried to storm the theater doors, Belsa, armed with a shotgun, forced them to retreat and stood guard for the rest of the night. (164) [7]

Upstairs in the Bijou was a young college freshman, recently enrolled at the University of Tennessee, who had stopped by the theatre for an evening of innocent entertainment whilst on a visit to the city to see his grandparents. Sixty years later, Clarence Brown was still emotional when he recalled how, from his vantage point in the theatre, he looked out on the street and saw “15 Negroes murdered by a goddamned mob of white men” (Eyman 23). [8]

Another whose life was shaped by the events of 22 September was Walter White, the future head of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and a firm supporter of Brown’s Intruder in the Dust many years later. Then 13 years old, White was travelling down one of Atlanta’s main thoroughfares, Peachtree St., when he caught a glimpse of

a lame Negro bootblack from Herndon’s barber shop pathetically trying to outrun a mob of whites. Less than a hundred yards from us the chase ended. We saw clubs and fists descending to the accompaniment of savage shouting and cursing. Suddenly a voice cried, “There goes another nigger!” Its work done, the mob went after new prey. The body with the withered foot lay dead in a pool of blood on the street. (W. White, A Man Called White 9)

White was very light-skinned and so managed to pass through the mob to safety but the next day he saw the stark evidence of the previous night’s events: “Like skulls on a cannibal’s hut the hats and caps of victims of the mob of the night before had been hung on the iron hooks of telegraph poles” (10). Just as Brown would be profoundly affected by the events of that night, only achieving some sort of cathartic relief when he made Intruder in the Dust, so too did witnessing the events of “terror and bitterness” serve to affirm Walter White’s identity (A Man Called White 11) and set him on a career committed to campaigning for racial equality.

A Man of the South

The night of 22 September certainly proved life changing for Brown, but it took him almost forty years to address the complexities of America’s attitudes to race on screen. The films he made in 1920s–1940s not only failed to engage with racial themes; they barely featured black characters at all. This omission was not especially unique to Brown: as historians such as Donald Bogle and Thomas Cripps have outlined, Hollywood films before the War generally steered clear of portraying race issues in any meaningful way and when black characters were included they tended to play menial roles or function as comic relief or musical interludes (Bogle;Cripps, Slow Fade to Black). This began to change during and after the Second World War when white America, fighting for democracy abroad, was forced to consider the baffling paradox of its own treatment of blacks. The emergence of a new generation of black writers and intellectuals such as Ralph Ellison, Carlton Moss, Richard Wright and Gwendolyn Brooks also served to intensify the calls for social and political change. It was in this context that Brown could finally make the film about race that had been germinating in his mind since the events of 1906. Screenwriter Ben Maddow admitted that he had been surprised that the right-wing, business-minded Brown seemed so personally invested in the project and so driven to make it, as if by doing so he could expunge a kind of collective guilt: “he told me he wanted to make amends for this part of his history that he could never forget” (McGilligan172). Yet even if Brown’s intentions were entirely honourable, and motivated by a genuine concern with portraying blacks sympathetically, he was also a man marked by the same prejudices and attitudes that defined his generation. Certainly, having grown up in Tennessee and spent the first years of his working life in Alabama—where he was involved in the motor car industry—he felt he could offer some insight into the complexities of the shifting dynamics of interactions between blacks and whites in the South. Just as Faulkner had done in all his work, Brown sought to capture both the intimacy and the gulf that existed between the races, yet if Faulkner’s Intruder in the Dust (1948) had allowed for allusions to the reality of miscegenation—the main black protagonist, Lucas Beauchamp, is proud of his white ancestry—Brown shied away from engaging with this subject, which he evidently considered taboo. No doubt this elision was, in large part, shaped by commercial pressure and by MGM’s desire to avoid potential censorship by Southern states—as Margaret McGehee has explored, both Lost Boundaries and Pinky had already fallen foul of Atlanta’s censor—but it seems that it was also a conscious choice on Brown’s part and one reflective of his own prejudices. In an unpublished interview he gave to Kevin Brownlow in the 1960s, he revealed his distaste for interracial relations (and his antiquated terminology) in a reference he made to a mild feud he had with actress Louise Brooks: “If I’ve been sour to Louise Brooks, it’s because she and Eddie Sutherland [her husband in the 1920s] didn’t draw the colour line. I’d seen darkies in their pool and I come from Tennessee! I’ve enough Southern blood not to be able to stomach that. I believe the Negro should get all he can hold, but I draw the line at the sex question”. In May 1949 in an interview he gave to Bob Thomas of the Associated Press to promote Intruder in the Dust, he was keen to reassure readers that his film would be entirely palatable to all audiences, especially as it avoided the subject of “black and white sex”.

Brown’s cautious approach proved invaluable when he travelled to Oxford in February to commence shooting: many in the town had a natural suspicion of “Hollywood folk” and were exceptionally sensitive about how they might be portrayed. [9] To oil the wheels, Brown highlighted his Tennessee roots and his healthy respect for business, telling the local newspaper The Oxford Eagle of the financial benefits the shoot would bring to the town, and promising that “with the cooperation of Oxford and Lafayette county people, we can make this film the most eloquent statement of the true Southern viewpoint of racial relations and racial problems ever sent out to the nation” (qtd. in Blotner 502). Brown’s message travelled fast and in neighbouring Tennessee the Memphis Commercial Appeal of 19 March 1949 reported that their native son was on a mission to promote a “better understanding of the true relationship between the South and of the gradualism which is solving this very old problem” (qtd. in Fadiman 30). [10] With such assurances and promises of monetary gain, locals got behind the film and became even more committed when Brown, cannily, cast several of them in small roles. [11] Yet for all his playing up of the role of a son of the South, one apparently content with the rules of segregation that prevailed in Oxford, it is to Brown’s credit—and a measure of his ambivalent attitude to race—that he later admitted to Scott Eyman that he faced the shoot with some trepidation, knowing the reception that his star, Juano Hernandez, was likely to encounter: “I apologized to him in advance for the way he was going to be treated down there. I am a Southerner and I know how they treat Negroes. I told him, ‘In Oxford, they’re going to treat you in ways you won’t like.’ He told me not to worry about it, he could control himself … He was quite a man” (23).

Figure 2: Juano Hernandez as Lucas Beauchamp in Clarence Brown’s Intruder in the Dust. MGM, 1949. Screenshot.

Brown was right to be concerned because the arrival of the self-assured, articulate Hernandez certainly presented the pillars of Oxford society with a dilemma: here was a black man who earned more in a week than most of them earned in a month, and yet could not be accommodated in the local hotel. In a defensive piece published by the Oxford Eagle shortly before the film’s premiere, writer Phil Mullen sought to assure readers (and, one assumes, the outside press that had travelled to the town to report on the film) that Hernandez had been perfectly content with the “natural” system of segregation and fitted right into Oxford ways: “Hernandez and the other visitors learned how false is most of the Northern publicity about Southern racial conditions ... Hernandez quickly agreed that he would follow the natural pattern of social segregation in his stay in Oxford … Just as he worked closely with director Brown and the white actors of the company, so he discovered that in Oxford Negroes and white men work closely together in all fields of endeavor and enjoy the same mutual respect and affection” (qtd. in Fadiman 35). [12] If the local press was keen to convey a sense that segregation was both natural and efficient, Hernandez offered a very different perspective in an interview he gave to Ebony in August 1949. Praising Brown, Faulkner and Maddow as “wonderful, fighting for the dignity of Lucas Beauchamp in every scene”, Oxford, he recalled, was another story: “I went down there with the idea of what I’d find and I didn’t get to change my mind” (qtd. in Fadiman 35). Perhaps the most revealing insight that Puerto-Rico-born Hernandez offered was that the prejudice he met with in Oxford was only a version of a more universal racism that operated in America: “nothing goes on in Oxford that doesn’t go on in New York City. I didn’t have to play at being Lucas Beauchamp. I’ve been him too many times” (qtd. in Fadiman 35–6). In an interview with the author, Claude Jarman Jr., who played Chick Mallison (the main character and narrator) in the film, confirmed that Hernandez did encounter some prejudice in Oxford but remembers that Brown and the rest of the cast and crew treated him with unfailing professionalism and deference; for Jarman’s part, he recalled being a little intimidated by the actor, whose air of self-assurance commanded respect (Jarman 2013). [13]

If Brown would produce a remarkable film in Intruder in the Dust, one that veritably marvelled at the authority and intelligence of its main black character and exposed the rottenness and dehumanising effects of racism (on both victim and perpetrator), he was still ambivalent in his attitude to black rights. In his interview with Philip Scheuer of the Los Angeles Times, published after the film’s premiere in Oxford, he was quoted as saying that he hoped Intruder in the Dust would “do a lot to set the South right in its thinking” but added, “that thinking must come from themselves … Without anti-lynch laws from Washington” (D1). It is interesting to note that when Intruder in the Dust was released in November 1949, one viewer, John Howard, wrote to the New York Times to express his disappointment that the film had failed to provoke a “stir inside”. For Howard, the problem lay in Brown’s (self) conscious striving to produce an eminently balanced film, which resulted in an overly objective, somewhat distant style, a “cold, impersonal attitude towards all the characters” (X8). While Howard seems to have been drawn to films that offered more sympathetic, “moving” characters (he contrasted Intruder in the Dust with Kazan’s Pinky and Werker’s Lost Boundaries), he was more perceptive than he might have imagined when he pointed to a certain coolness on Brown’s part. What may ultimately be one of the film’s greatest strengths—Brown’s dispassionate, somewhat detached style that bears witness to an astonishing performance by Hernandez and calmly, but devastatingly, exposes the ugly facts of racism—is perhaps also a mark of Brown’s own ambivalence about just where he stood on matters of race. It is perhaps this uncertainty, and the implied acknowledgement of his dual status as both an insider (who understood Southern ways) and an outsider (who, having left the South in the 1910s, had had plenty of time to mull over his experiences there and to confront his own—still-held—prejudices) that made Intruder in the Dust the most complex of all the race films released in 1949 and the only one that earned the respect of both the white and the black press.

The Critical Reception of Intruder in the Dust

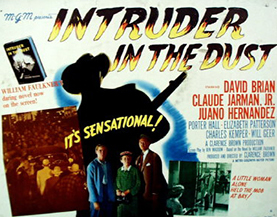

MGM and Brown publicised the film as one that could please all sections of the audiences, from the white South—Brown predicted to Bob Thomas that “[there would be] no trouble from its showing the South” because the “the folks in Oxford liked the story, and the Negro actors in the cast thought it was great”—to “the Commies” (“I can’t see what they can object to”) (Thomas). MGM’s advertising generally played down the racial themes, in favour of the murder-mystery angle that centred on exposing the real perpetrator of the murder of the white Vinson Gowrie (of which Lucas is accused).

Figure 3: Original lobby card advertising Intruder in the Dust. Author's collection.

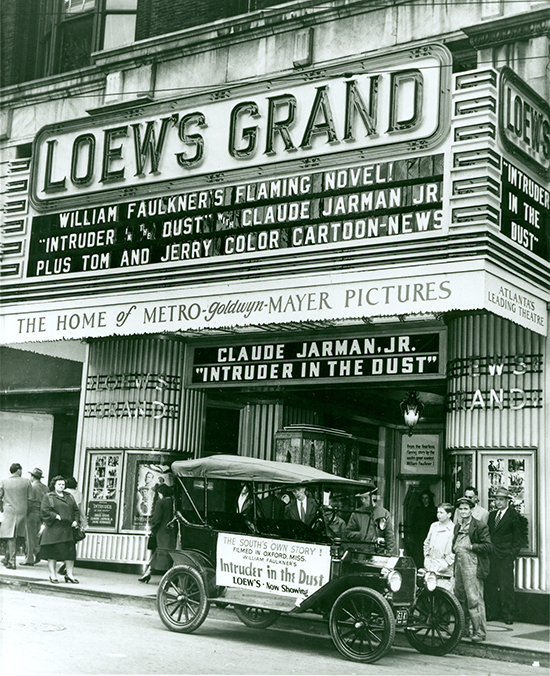

In the South, MGM’s promotional campaign emphasised that the film was Southern- produced, from a novel by the South’s own son, William Faulkner, and featuring Tennessee-born (or raised) actors (Claude Jarman Jr. and Elizabeth Patterson) and directed by Knoxville-native, Clarence Brown.

Figure 4: Photo showing how Intruder in the Dust was advertised at Loew’s Grand Theater, Atlanta. Note the car heralding the film as “The South’s Own Story”. Photo from Author’s collection.

The campaign evidently worked, as the response in Southern newspapers was mainly positive, although somewhat guarded. Some (white) reviewers chose to disavow the racial critique, praising the film as a suspenseful “whodunit”: Ben S. Parker, writing in the Memphis Commercial Appeal of 12 October 1949 called it a “crisply paced taut whodunit set against the leisurely background of a Southern town”, but hastily added that Hernandez’s character was “hardly typical of the Southern Negro” (187). In Louisiana, the reviewer for the New Orleans Item tried to turn Lucas into a folksy, humorous (non-threatening) character, a “cantankerous, bigoted old Negro, independent as a hog on ice” (“Intruder in the Dust”), while a hint of white paternalism may be detected in W. F. Minor’s account of the film’s premiere and its content: praising Lucas as a “proud, self-reliant Negro” who is determined to “pay his way and not accept the crumbs of the paternalistic white man”, Minor nevertheless points out the film is a timely reminder to the (white) South of “its responsibilities toward the racial minority in its midst” (31). Fairfax Nisbit, writing for the Dallas Morning News, was pleased that the film packed a “good sound punch as a whodunit” and even more pleased that while it was “another treatment of the racial question” it was “not from social equality angle so popular with Northern zealots” (15). Other reviewers were a little more reflective: in her piece for the Charlotte News, Emily Wister admitted “the South, particularly Mississippi, comes in for some hearty slaps in this picture and the sad thing about it is most of the charges are true”.

Most scholars that have written about Intruder in the Dust’s critical reception have concentrated on examining selections from the national press and from a handful of regional and black newspapers. Fadiman, among others, has singled out Ralph Ellison’s analysis of the four race issue films of 1949, which he filed for The Reporter in December 1949, as being representative of the positive response the film provoked in the black press (18). Certainly, Ellison’s article is perceptive and offers a crucial insight into how the race issue films produced by (white) Hollywood played among black audiences. He argued that all four films released that year were compromised in varying degrees, united in the cautiousness with which they approached the key issues of integration and equal rights, and offering sometimes naïve portrayals of racial identity. For Ellison, Hollywood’s “Negro movies” were “not about Negroes at all; they are about what whites think and feel about Negroes” (18; emphasis in original). They should be seen, he posited, as serving a cathartic function for white audiences—an observation that, for this article, is most pertinent—but for black audiences they would invariably have an entirely different meaning. While Ellison was rather dismissive of Hollywood’s efforts to deal with the “race problem”, he conceded that one of the four films, Brown’s Intruder in the Dust, was more complex and “could be shown in Harlem without arousing unintended laughter. For it is the only one of the four in which Negroes can make complete identification with their screen image” (19). Yet just how much did white and black viewers identify with what they saw on screen and how accurate is the now widespread perception that black audiences embraced the film? Archer Winston, a white columnist for the New York Post, filed one of the few extant accounts of how the film was received before a live audience. [14] Watching the film in the company of both white and black moviegoers in the Mayfair Theater in New York, he noted that the film seemed to be much more enthusiastically received by the black members of the audience than by the whites. Concluding that this film would “appeal powerfully to Negroes and would mean much less to whites” he qualified this by pointing to some reservations among the black audience as some that he canvassed after the screening had expressed disappointment that “they [i.e. the filmmakers] didn’t show enough [of] racial conflict” (37).

In his study of the postwar message movie—i.e. Hollywood productions that explicitly tackled the “issues” of the day, such as anti-Semitism, racism etc.—film historian Thomas Cripps has noted that the positive notices that Intruder in the Dust garnered in mainstream black and white press “constituted a striking consensus of black and white agreement on newly defined terms of postwar racial arrangements rooted in neither empty nostalgia nor interventionism” (Making Movies Black 243). While Cripps’s statement certainly suggests that the critical reception of Intruder in the Dust was largely uncontentious, the content palatable for even the most conservative—and the most radical—sectors of the audience, a closer examination of the black press reveals the fissures and debates that the film’s treatment of race and racism provoked. As Anna Everett has examined in her study of black film criticism from 1909–1949, the decade saw the development of an increasingly engaged and more militant black intelligentsia whose impatience with the slow pace of change and Hollywood’s persistence in using stereotypes was expressed in their writings on film. A survey of some of the reviews of Intruder in the Dust in the black press reveals that the film divided critics more than it has generally been acknowledged. Those who responded positively included Lillian Scott of the venerable Chicago Defender who offered praise for Brown’s pared down style and the visual symbolism used to depict the “cancerous tissue of Southern life” (26). Scott was particularly thrilled by Hernandez as the “unbending Lucas striding down the street with his broad belt, swallowtail coat, preacher’s hat and gold toothpick ... he is never a ludicrous figure” (26). Lawrence F. LaMar, writing in The Washington Afro-American of 15 November 1949, called it a “stirring story” and commended Brown for his personal commitment in bringing it to the screen. For LaMar, Hernandez’s Lucas Beauchamp was a rare portrayal of strong black masculinity and he urged his readers to attend: “this picture is strictly a ‘must’ for men … who feel inclined to reach the full measure of courageous manhood despite racial handicaps. To them, this character points the way” (6). Over at the Pittsburgh Courier the reviewer was excited by the positive reaction that the film had received at a preview screening where only two audience members objected to it but “they were from the South and were prejudiced” (18). Two Southern black-managed newspapers, the Atlanta Daily World and the Mound Bayou News-Digest in Mississippi(a newspaper produced in a town that originated as an ex-slaves settlement) ran several appreciative pieces on the film. Ruby Berkeley Goodwin, in a general article on the four race issue films, suggested that her readers should move on from pointing out the films’ flaws and instead “get the cramp out of your arm and write them [the Hollywood studios] your appreciation for the recognition they have accorded the Negro” (2). The Atlanta Daily World praised it as an “absorbing motion picture study in mob violence” in which “Hernandez is an indomitable figure” (“Hernandez Stars” 8), an actor who “made it a living real role and one he can always look back on with pride” (A. White 4). One of the most influential commentators on the film was Walter White, then head of the NAACP. He had served as a consultant on film and had, like Brown, witnessed the 1906 riots first hand. Writing in his column for the Chicago Defender, he called Intruder in the Dust “one of the most honest and effective exposes of bigotry ever made” (7).

Yet support for the film was not entirely unanimous among the black community and the expressions of dissent offered by some are perhaps revealing of more general tensions between two generations of black intellectuals. The California Eagle, a black newspaper that was more politically left wing than most, is a particularly illuminating source and one newly accessible through online sources (e.g. www.archive.org). No doubt aware of the newspaper’s large readership and interest in moviegoing, MGM took out ads for the film in it and, in turn, the newspaper devoted several columns and reviews to the production. In his entertainment column of 17 November 1949 Bob Ellis praised it as a “dynamic movie”, a “smashing weapon against intolerance and a body blow at the very people who appear in all the minor and extra roles” (15). For Ellis, never had “a more damning indictment of the Southern white middle-class and mob … come from the screen in its history” and he wryly pointed out that “only an egotistical, stubborn group of people who don’t care what the rest of the world thinks of them, could consent to appear in a film showing their true bigotry and hate” (15). Positive though the review was, Ellis didn’t shy away from offering some negative criticism, expressing disappointment that Brown’s direction of Emmanuel in the graveyard scene was “cruel” (15). Ellis’ review evidently prompted Brown to write to him directly, because the following month the critic quoted from the letter he had received from Brown in which the director admitted that “it is no secret that we did not quite see eye to eye before the picture … but after your review, I felt we saw eye to eye clearly” (15). Black and Brown seemed united, and Ellis offered a note of thanks to the director: “you didn’t climb on the bandwagon … Therefore your personally produced and directed picture is a tribute to your understanding of what the Negro in this country suffers. Moreover, you had the courage to do something about your ideas” (15). Ellis finished his column by calling on Brown to lead the charge against “Un-American pattern” of Hollywood’s unofficial adherence to the Jim Crow system and to start employing blacks (15).

Yet if Ellis offered glowing endorsements in the California Eagle, his colleague at the newspaper, John M. Lee, offered a dissenting view, which, to the newspaper’s credit, they printed. In his column, dated 24 November 1949, he categorised Intruder in the Dust with the other four race films, and claimed they only saw the light of day because the studios had finally recognised the “untapped wealth sources in stories about Negros” (7). All four race films “as revolutionary as they seem to appear”, were, he asserted, “nothing more than representations of condescension from men who know something has been wrong, but who do not care to disturb the balance too much.” He accused Intruder in the Dust of being “a devious picture with a devious purpose” that offered an endorsement of “what apologists for the backward South have been saying for generations. It says only the unwashed, ignorant white trash make up the lynch mobs. It says the ‘good’ white folks in the South can take care of the Negro problem without any help from outsiders” (7). He finished by claiming that the “type of Negro the picture portrays is the type of Negro that the South has been trying to create since the Civil War; a Negro with bastard ties to the white community, who considers himself apart from the pure blacks, and a Negro who idolizes white folks” (7). While his review is not always factually accurate, it is a provocative analysis and perhaps a fitting conclusion to this article: for Lee, at least, the problem with Intruder in the Dust was that, while it undoubtedly represented a strong black man in a central role, Lucas was just one man, apart from others of his race. Ultimately, the film seemed to endorse the conservative ideology of gradualism: that the South would eventually change in its attitudes to racial equality and that the significance of a figure like Lucas Beauchamp was in his role as a “keeper of the conscience” of white folks who, in time, would bestow rights upon him. For the younger, more politically engaged generation of black writers and activists, of which John Lee was representative, it was simply too late for such a cautious approach; instead, the future lay in collective action by the black community (of which there was little sign in either novel or film).

And as a coda, it is tempting to speculate that some of the inhabitants of Oxford—who took their time to be “won over” by the Hollywood folk but, given their fifteen minutes of fame on the screen and cash in their registers, went on to proudly assert that Intruder in the Dust was “the South’s own story”—must have turned out to heckle and intimidate James Meredith when, 14 years after Brown and his crew had left the state, he arrived in the University of Mississippi’s Oxford Campus to take up his place in university, and by doing so, kick-start that state’s slow movement towards racial integration.

Notes

[1] Intruder in the Dust has been subject to some critical attention, most notably a full-length study by Regina Fadiman (which also reprints Ben Maddow’s script), and articles that offer close analysis of both the novel and film (and the process of adaptation) by Dorothy B. Jones, Pauline Degenfelder, Stephanie Li and Charles Hannon. Thomas Cripps, in his study of the Hollywood message movie, has also examined it within the context of a discussion on the four big “race issue” films of 1949 (see Cripps, Making Movies Black especially pages 241–49). I have also analysed the film, and touched upon the issue of Brown’s Southern roots, in an article for The Journal of East Tennessee History. My focus here is on two specific aspects: the wider critical reception of the film in the black, white, national and regional press, and on how Brown’s experiences in Atlanta in 1906, and his background in the South, influenced his decision to champion the project.

[2] Carter was a Pulitzer prizewinning journalist who wrote many editorials on the South and earned a reputation for progressive views on the issue of race.

[3] With the exception of one loan-out to Twentieth-Century Fox for The Rains Came (1939), all of Brown’s films from 1926 on were made for MGM. It has sometimes been suggested that the friendship between Brown and Mayer might have led to a certain perception of Brown as simply a studio lackey, one whose work was undeserving of much critical attention. Undoubtedly, when the first wave of auteur-based studies of directors such as Howard Hawks, John Ford, Orson Welles, Allan Dwan etc., was being published in the 1960s and 1970s, Brown’s career was largely ignored.

[4] His conservatism was in contrast to the other directors that helmed the other big “race issue” films of the year—all of whom had stated their preference for liberal politics.

[5] Larkin married Irish-born Catherine Gaw around 1889 and Clarence was born on 10 May 1890 in Clinton, Massachusetts, where Larkin was working as a supervisor at the local textile mills.

[6] One source estimates that the black population was around 40% in 1900 (Ambrose).

[7] Here, the similarities between Belsa’s actions and Will Legate’s in Faulkner’s Intruder in the Dust are striking. Crowe also recounts a reported incident of a “very frail white woman” who bravely saved “a black man from a hundred assailants merely by standing before her door and ‘refusing’ to allow anyone to cross her threshold until the police arrived” (“Racial Massacre” 164). It seems even the most vicious mob could be stopped in its track by a shared sense of Southern chivalry and deference to white women. While there’s no firm evidence to suggest that either Brown or Faulkner had read this account and that it influenced their depiction of Mrs. Habersham (who, armed only with her knitting, sees off the bloodthirsty mob that arrives to lynch Lucas), it is certainly an astonishing coincidence. As Southerners, there is no doubt that both Faulkner and Brown would have been very familiar with, and had witnessed scenes of, racial violence (Faulkner was partly inspired by the case of the lynching of Nelse Patton, which he witnessed when he was 10, for his story of Lucas Beauchamp in Intruder in the Dust (and indeed similar incidences in a number of his novels. See Blotner).

[8] Brown elaborated (and embellished, given Crowe’s estimate of black fatalities) on what he saw in unpublished interviews with Kevin Brownlow in 1966: “I saw this [the riot] with my own eyes. There were 150 negroes killed that weekend. It left an indelible impression. The poor innocent negroes would come in out of the country on Saturday night in the streetcar to do their shopping, and the mob would drag them off the streets. They didn’t know what the hell’s happening”.

[9] Many Southerners had objected to earlier Hollywood adaptations of Faulkner novels—notably Paramount’s 1933 version of Sanctuary, released as The Story of Temple Drake.

[10] No doubt Brown was eager to send out a loud message to Memphis’ notoriously difficult censor, Lloyd T. Binford. It evidently worked: when the film was sent to him for vetting, he approved it, albeit grudgingly, complaining that it “doesn’t live up to southern ideals” (LeFlore 26).

[11] In “An Honest Presentation”, penned by Hodding Carter for his home newspaper, the Delta Democrat-Times in Greenville, Mississippi, he noted how much attention to detail the production was paying in its location work in Oxford, and its involvement of several members of the local community (4).

[12] While Brown certainly seems to have won over the townspeople and indeed offered a devastating portrait of their casual racism—for instance, a scene in which the real-life mayor, R. X. Williams, plays a respectable member of the community, who offers to help out in the lynching of Lucas—he could not win the battle over Hernandez’s accommodation: while the rest of the cast and crew stayed at the local hotel, the film’s star was lodged in a local (black) undertaker’s home. More on Hernandez and his extraordinary life can be found in Levette’s profile published in The Afro-American.

[13] Yet, according to Fadiman, Elzie Emanuel, who played Aleck Sander, Chick’s black friend (and son of the Mallison family’s housekeeper), was apparently unhappy with the way that Brown handled one scene, in which Aleck and Chick dig up the grave of Vinson Gowrie. Reportedly, Brown overruled Emanuel’s objections to the stereotyping of his reactions—in comic coon fashion he rolls his eyes and becomes near-hysterical—and retained a scene that would provoke much negative criticism from the black press (see Fadiman 36).

[14] There are, of course, some accounts of the reception of the film at its premiere in Oxford but these mainly concentrate on how delighted everyone was with the film, and with their (minor) appearances in it.

References

1. Ah Wilderness! Dir. Clarence Brown. MGM, 1935. Film.

2. Ambrose, Andy. “Atlanta”. Ed. NGE Staff. New Georgia Encyclopedia 11 Nov. 2013. Web.

<http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/counties-cities-neighborhoods/atlanta>. 8 Dec. 2013.3. “A Surprise—Faulkner Meets the Press”. The Memphis Press Scimitar 12 Oct. 1949: 17. Print.

4. Bogle, Donad. Toms, Coons, Mammies, and Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Films. New York: Continuum, 1989. Print.

5. Blotner, Joseph (1974). Faulkner: A Biography. Jackson:U.P. of Mississippi, 2005. Print.

6. Brownlow, Kevin. Unpublished Interview with Clarence Brown. Paris 1966. TS. The Kevin Brownlow archive, London. n. pag.

7. Carey, Gary. All the Stars in Heaven: The Story of Louis B. Mayer and M.G.M. London: Robson Books, 1981. Print.

8. Carter, Hodding. “An Honest Presentation”. The Delta Democrat-Times 24 Apr. 1949: 4. Print.

9. ---. “No Phony Magnolias”. The Washington Post 1 May 1949: B7. Print.

10. Chapman, James, Mark Glancy, and Sue Harper, eds. The New Film History: Sources, Methods, Approaches. London: Palgrave Macmillian, 2007. Print.

11. Cripps, Thomas. Slow Fade to Black: The Negro in American Film, 1940–1942. Oxford: Oxford U.P., 1979. Print.

12. ---. Making Movies Black: The Hollywood Message Movie from World War II to the Civil Rights Era. Oxford: Oxford U.P., 1993. Print.

13. Crowe, Charles. “Racial Violence and Social Reform: Origins of the Atlanta Race Riot of 1906”. Journal of Negro History 53 (July 1968): 234–56. Print.

14. ---. “Racial Massacre in Atlanta, September 22, 1906”. Journal of Negro History 54 (Apr. 1969): 150–73. Print

15. Crowther, Bosley. “The Screen in Review; ‘Intruder in the Dust’”. New York Times. 23 Nov. 1949: 19. Print.16. D.C. “Hints from Hollywood. Sound—And Silence”. Movie Makers 25, Jan.–Dec. 1950: 24. Print.

17. Degenfelder, Pauline. ‘The Film Adaptation of Faulkner’s Intruder in the Dust”. Literature/ Film Quarterly 1(Spring. 1973): 138–48. Print.

18. Ellis, Robert. “Hollywood at Dawn”. The California Eagle 17 Nov. 1949: 15. Print.

19. ---. “Hollywood at Dawn”. The California Eagle 5 Dec. 1949: 15. Print.

20. Ellison, Ralph. “The Shadow and the Act”. The Reporter 6 Dec. 1949: 17–19. Print.

21. Everett, Anna. Returning the Gaze: A Genealogy of Black Film Criticism, 1909–1949. Durham: Duke U.P., 2001. Print.

22. Eyman, Scott. “Clarence Brown: Garbo and Beyond”. The Velvet Light Trap 18 (Spring 1978): 19–23. Print.

23. Fadiman, Regina B. Faulkner’s Intruder in the Dust: Novel Into Film. Knoxville: U. of Tennessee P., 1979. Print.

24. Faulkner, William. Intruder in the Dust. New York: Random House, 1948. Print.

25. Goodwin, Ruby Berkeley. “Bronze”. The Mound Bayou News-Digest 13 May 1950: 2. Print.

26. The Goose Woman. Dir. Clarence Brown. Universal, 1925. Film.

27. Hannon, Charles. “Race Fantasies: The Filming of Intruder in the Dust”. In Faulkner in Cultural Context, eds. Donald Kartiganer and Ann Abadie. Jackson: U.P. of Mississippi, 1997. 263–83. Print.

28. “Hernandez Stars in ‘Intruder in the Dust’”. The Atlanta Daily World 3 Dec. 1949: 6. Print.

29. Home of the Brave. Dir: Mark Robson. Stanley Kramer productions/United Artists, 1949. Film.

30. Howard, John. Letter. New York Times. 4 Dec. 1949: X8. Print.

31. The Human Comedy. Dir. Clarence Brown. MGM, 1943. Print.

32. Intruder in the Dust. Dir. Clarence Brown. MGM, 1949. Film

33. “‘Intruder’ Gets Good Notices”. The Pittsburgh-Courier 13 Aug. 1949: 18. Print

34. “Intruder in the Dust” (review). The New Orleans Item 4 Nov. 1949. Clipping in the Clarence Brown Archive, University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

35. Jarman Jr., Claude. Personal Interview. 3 May 2013.

36. Jones, Dorothy B. “William Faulkner: Novel into Film”. Quarterly of Film, Radio and Television 8 (Fall 1953): 51–71. Print.

37. LaMar, Lawrence. “‘Intruder in the Dust’ is Stirring Story of Intolerance”. The Washington Afro-American 15 Nov. 1949: 6. Print.

38. Lee, John M. “All Things Considered…”. The California Eagle 24 Nov. 1949: 7. Print.

39. LeFlore, John. “‘Intruder in the Dust’ Escapes Ban”. The Chicago Defender 24. Sep. 1949: 26. Print.

40. Levette, Harry. “Actor Juano Hernandez Doubles as a Teacher”. The Afro-American 16 Jul. 1955: 7. Print.

41. Li, Stephanie. “Intruder in the Dust from Novel to Movie: The Development of Chick Mallison”. The Faulkner Journal XVI (Fall 2000/Spring 2001): 105–118. Print.

42. Lost Boundaries. Dir. Alfred L. Werker. Louis de Rochemont Associates, 1949. Film.

43. “Mae Tinee”. “Review of Intruder in the Dust”. Chicago Daily Tribune 27. Feb. 1950: B7 [Mae Tinee was a pseudonym used by a variety of writers at the newspaper]. Print.

44. McGehee, Margaret T. “Disturbing the Peace: ‘Lost Boundaries’, ‘Pinky’, and Censorship in Atlanta, Georgia, 1949–1952” Cinema Journal 46.1 (Autumn 2006): 23–51. Print.

45. McGilligan, Patrick. “Ben Maddow: The Invisible Man”. Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s. Berkeley: U. of California P., 1997. 157–93. Print.

46. “Negroes Movie-Conscious; Support 430 Film Houses”. Motion Picture Herald 24 Jan. 1942: 33. Print.

47. Minor, W.F. “‘Intruder in the Dust Premiere Held at Oxford”. The Times-Picayune 12 Oct. 1949: 31. Print.

48. Nisbit, Fairfax. “Gripping Whodunit with Racial Problem Angles”. Dallas Morning News 10 Feb. 1950: 15. Print.

49. Of Human Hearts. Dir. Clarence Brown. MGM, 1938. Film.

50. Parker, Ben S. “Review: ‘Intruder in the Dust’”. The Memphis Commercial Appeal 12 Oct. 1949: 187. Print.

51. Pinky. Dir. Elia Kazan. Twentieth Century Fox, 1949. Film.

52. The Rains Came. Dir. Clarence Brown. Twentieth Century Fox, 1939. Film.

53. Rotha, Paul. Letter to Clarence Brown. 25 Mar. 1950: 1. TS. Clarence Brown archive at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

54. Schallert, Edwin. “‘Intruder in the Dust’ Grimly Courageous”. The Los Angeles Times 12 Nov. 1949: 11. Print.

55. Scheuer, Philip. “Brown Champions Work on Location”. The Los Angeles Times. 30 Oct. 1949: D1; D4. Print.

56. Scott, Lillian. “‘Intruder in the Dust’ Puts Hernandez in ‘The Tops’ Class”. The Chicago Defender 26 Nov. 1949: 27. Print.

57. Signal Tower, The. Dir. Clarence Brown. Universal, 1924. Film

58. The Story of Temple Drake. Dir.Stephen Roberts. Paramount, 1933. Film.

59. Thomas, Bob. “Director tells of Making Picture on Negro Theme”. Associated Press, reprinted in Toledo Blade 10 May 1949. Clipping in the Clarence Brown Archive, University of Tennesee, Knoxville. N. pag. Available online. <http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1350&dat=19490510&id=PfVOAAAAIBAJ&sjid=EQAEAAAAIBAJ&pg=1937,4065776>.

60. White, Alvin. “N.Y. Critics Rate Star of ‘Intruder’ Year’s Runnerup”. The Atlanta Daily World. 4 Jan. 1950: 4. Print.

61. White, Walter (1948). A Man Called White: The Autobiography of Walter White Atlanta: U. of Georgia P., 1995. Print.

62. ---. “An Epilogue is Needed for Two Popular Screen Stories”. The Chicago Defender 8 Apr. 1950: 7. Print.

63. Winston, Archer. “Intruder in the Dust”. The New York Post. 6 Dec. 1949: 37. Print.

64. Wister, Emily. Review of “Intruder in the Dust”. The Charlotte News 23 Jan. 1950. N. pag. Clipping in the Clarence Brown Archive, University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

65. The Yearling. Dir. Clarence Brown. MGM, 1947. Film.

66. Young, Gwenda. “Brown: From Knoxville to Hollywood and Back”. The Journal of East Tennessee History 73, 2002: 53–73. Print.

Suggested Citation

Young, G. (2013) 'Exploring racial politics, personal history and critical reception: Clarence Brown's Intruder in the Dust (1949)', Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 6, pp. 51–68. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.6.04.

Gwenda Young lectures in Film Studies in University College Cork and is Co-director of the Film and Screen Media programme there. Her work has appeared in a variety of national and international journals, including Sight and Sound; Popular Culture Review; Film/Film Culture; Film Ireland; Journal of Irish Association for American Studies and in edited collections on American cinema of the 1920s and Irish American cinema. She has also contributed to radio programmes on the national broadcaster, Raidió Teilifís Éireann, on local radio, and on Irish national television. Her monograph on American director Clarence Brown will be published in 2014.