"A Taste in Pictures": The Second Birth of Cinema in Cork

Denis Condon

[Abstract] [PDF]

“That cinematography is entering more and more into the everyday life of the community is an obvious fact”, wrote Irish Independent literary critic Terence O’Hanlon in December 1913. “Already it is playing an important part in commerce and education, in addition to its merits as a public entertainer” (4). Writing for a mainstream Irish Catholic nationalist audience at Christmas, O’Hanlon chose to discuss picture houses—a rival at the Freeman’s Journal was reviewing the poems of Irish literary revivalist Dora Sigerson Shorter—offering insight into the place that cinema was coming to hold in Irish society in the early 1910s (“Current Literature” 2). It was obvious to the Dublin-based O’Hanlon in 1913 that the picture house had become an important element of everyday life in Ireland, and such a fact was worth addressing at this significant time of the year. However, rather than giving an overview of the situation in the country—he said nothing about Cork, on which this article will focus—he devoted most of the article to recounting interesting facts and anecdotes from the cinema business around the world. Nevertheless, he clearly intended to give a positive account of cinematography—meaning the institution of cinema—that justified his attention to it, concluding by stressing commerce and education, elements beyond mere entertainment that were likely to be of interest to the column’s main readership: middle-class Catholic nationalists with an interest in cultural matters.

Although this lived experience of cinema may have been obvious in 1913, its lack of representation in O’Hanlon’s article and elsewhere makes it difficult to recapture at a distance of a century. It can be glimpsed to some extent by a close attention to the use of what may seem to be a quaint and obsolete terminology. O’Hanlon’s use of “picture house” and “cinematography” is a case in point. In the later twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, both of the phenomena that he refers to would most commonly be termed “cinema”. O’Hanlon’s terminology—typical of the time—helps draw a distinction that is crucial to the argument that follows between the picture house—a new kind of entertainment venue whose novelty was that it mainly showed filmed entertainment—and cinematography or cinema—the cultural institution that must exist for a picture house business to be sustainable: filmmaking and distribution, certainly, but also such locally negotiated elements as regulation, and adoption by people who come to self-identify as picture house goers, that is, the audience.

To return to the date of O’Hanlon’s article, December 1913 is significant for other reasons connected to class, political ideology and the Irish Independent, given that newspaper’s interested involvement in the prolonged labour dispute known as the Dublin Lockout. The Irish Independent adopted an editorial line on the Lockout that reflected its ownership by William Martin Murphy, the leader of the employers who sought to stop the growing power of Jim Larkin’s Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union. These facts are not likely to be missed by anyone living in the Republic of Ireland in the present historical moment, given the prominent place in the Irish mediascape of what some cultural administrators have termed the DOC, the Decade of Centenaries that began in 2012 and that in 2013 is particularly focused on labour issues raised by the centenary of the Lockout (Government of Ireland). In this context, the praise of cinema by the Irish Independent takes on a different complexion, prompting questions about the place of the new medium of cinema in the Irish mediascape of the 1910s and where it might be located in relation to such obvious class conflict.

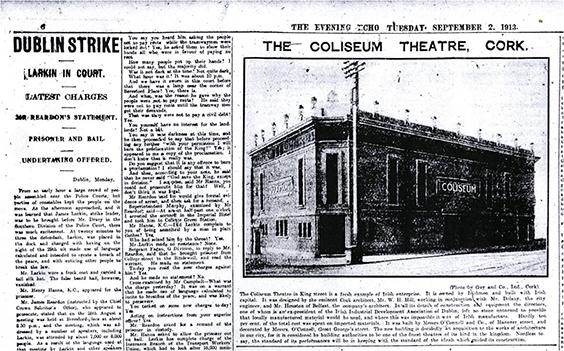

Indeed, the Lockout forms the backdrop for the opening in September 1913—a date that seems inevitably to recall W. B. Yeats’s poem of that name on Irish culture and politics—of the 800-seat Coliseum Picture Theatre in Cork’s King (now MacCurtain) Street. As the publicity campaign for the opening of the Coliseum began on 1 September, all Cork’s newspapers also reported in detail on the dramatic developments in the strikes in Dublin, especially the baton-charging of workers’ protests by the Dublin Metropolitan Police on 30 and 31 August that led to the death of two workers and the injuring of hundreds more. Alongside its report on Larkin’s trial for addressing a proclaimed rally, Cork’s Evening Echo published a large photograph of the soon-to-be-opened Coliseum, accompanied by a commentary that focused on the Irishness of the design, construction, fitting out and ownership of the building (Figure 1). Although this juxtaposition makes no actual connection between these stories beyond indicating that the editor thought it appropriate to place these articles on shifts in class politics and cinema side by side, it raises questions about the degree to which cinema related to such developments in everyday life in Ireland, particularly in Cork, and about what newspapers can tell us of the cinematic past.

Figure 1: The general strike in Dublin is reported alongside opening of the Coliseum Picture Theatre. Evening Echo 2 Sep. 1913: 6; courtesy of the Evening Echo.

In focusing on the growing importance of cinema at national and local level, the Irish Independent and Evening Echo articles draw attention to a fundamental cultural change that was occurring in Ireland in the early 1910s. The arrival of the cinema as a permanent feature of urban and rural Ireland began about 1910 and continued until at least 1914, when the First World War slowed the seemingly ever-increasing pace in the construction of picture houses. In a very short period after 1910, the way that many ordinary Irish people spent their leisure time changed fundamentally. The process began earliest in the cities of Dublin and Belfast, where dozens of cinemas sprang up in the centres and suburbs to meet the burgeoning demand for moving pictures. However, the changes to the way people spent their leisure time were particularly clear in provincial towns. The larger populations of the cities supported many types of entertainment and leisure activities that could be enjoyed any night of the week, but in towns and rural areas, professional and even amateur entertainment had typically been sporadic and did not encroach very significantly on the business of provincial Ireland’s main leisure provider: the public house. By 1914, however, an extraordinary transformation had taken place not only in the cities but also in Irish towns of any size, where for the first time ever people could, if they could afford the often very modest ticket price, attend nightly, professionally made entertainment. In many places, they could choose to which of the town’s moving-picture shows they would go.

The most pertinent concept for characterising this sudden and momentous change is André Gaudreault and Philippe Marion’s notion of a “second birth” of cinema. Gaudreault and Marion contend that cinema exemplifies a double birth that all media undergo to attain an autonomous identity (4). A medium’s first birth produces the basic apparatuses, which in cinema’s case are the camera, film printer and projector that were available by 1895. However, the invention of such technologies is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the existence of a medium, which must await the emergence of the cultural practices and conventions that define how the technology should be used. While this occurs, the medium does not exist as such; it is an “intermedium” defined by the practices of existing media but also altering them in the process. Wishing to avoid the unwelcome retrospective connotations of the word “cinema” altogether, Gaudreault has termed the many uses of projected moving pictures during this period “kine-attractography” (Gaudreault, “From ‘Primitive Cinema’” 94). Eventually, a series of practices said to be specific to the basic apparatuses is identified, allowing the new medium to be constituted as an autonomous institution. This results in a second birth of a medium that is now identified as independent of those with which it had previously been identified.

Although from the perspective of Ireland the invention of the cinematic apparatuses and the defining of autonomous practices for their use occur elsewhere, the second birth of cinema relies on the adaptation of these practices at national and local level. The focus here will be the process of local adaptation in Cork of a cinematic medium already largely constituted elsewhere. Therefore, this is a work of local cinema history and not of film history, to emphasise the distinction that theorists of the new cinema history make between older film histories centred on “an aesthetic history of textual relations between individuals or individual objects” and newer forms of analysis concerned with such issues as “the cinema as a commercial institution and with the sociocultural history of its audiences” (Maltby and Stokes; Maltby 9). Given that, in the 1910s, most films were screened for just three days, any individual film—no matter how outstanding it may seem in retrospect—would have had very limited effect on its audiences relative to the regular habit of going to the pictures experienced over decades. A history of films has little to say about how and why cinema was entering increasingly into the everyday life of such Irish communities as Cork.

Local conditions in the city were crucial to this process. Located on Ireland’s south Atlantic coast, Cork was the most populous city in the southern province of Munster, with a population of 76,673 in the 1911 Census, making it the third largest urban area in Ireland after Belfast with 386,947 and Dublin with 304,802, both of which also had substantial suburbs and satellite towns. It is situated on the River Lee, whose north and south channels make the city centre an island. Without a local supply of coal, Cork—like much of Ireland outside the north-east—lacked the heavy industry of the nineteenth-century industrial revolution and, as a result, the city really only experienced economic growth in such industries as “brewing, distilling, butter, bacon and tanning” (Stack 178). Many of these relied on the city’s rich agricultural hinterland and the export opportunities offered by ready access to the sea.

The River Lee was navigable by shipping as far as the city’s quays, but Cork harbour further downriver also had sheltered deepwater berths at Queenstown (now Cobh), “the last important harbour on the West of Europe, that is to say, the first to be reached from the New World” (Coakley 43). Queenstown was famously the Titanic’s last port of call in 1912, but it was also one of the most important embarkation points for the millions of Irish people who emigrated to North America not only during the disastrous Famine of the 1840s but in the century that followed. Developments in the steamship trade meant that by the turn of the century the flow of people was not completely one way; the reduction of the transatlantic crossing to less than a week facilitated tourism. Several filmmakers travelling between North America and Europe stopped off at Cork and shot films at the world-famed Blarney Castle, located a short distance from the city, or travelled to the even more famous Lakes of Killarney in the neighbouring County Kerry. Particularly significant among those who made films in the early 1910s were Vitagraph star John Bunny, who made Bunny Blarneyed (1913) in Cork in 1912, and the Kalem filmmakers led by director Sidney Olcott, who shot in the city during their annual visits to Killarney between 1910 and 1914 (O’Kalem Collection; Condon, “Century”).

Politics and religion shaped—and were shaped in turn—by the city’s media. Politically, Ireland had, since 1801, been a part of the United Kingdom, with members of Parliament at Westminster, but the main political question in Ireland since the late nineteenth century was whether or not the country should have Home Rule, a form of limited legislative independence. The supporters of Home Rule were predominantly—but not exclusively—Catholics, who made up more than 80% of the Irish population as a whole and 87% in Cork, while political supporters of the Union with Britain were predominantly Protestant. The press in Cork—as elsewhere in Ireland—reflected these ideological divisions. A timely example of this was the Cork Free Press, one of the city’s three morning newspapers, which was founded in 1910 specifically as a vehicle for William O’Brien’s All-For-Ireland League, a faction of Irish nationalism. This ideological editorial line of a Home Rule Ireland was shared with Cork’s most popular newspaper, the Cork Examiner—which along with its Evening Echo supported John Redmond’s Irish Parliamentary Party—but the Free Press and Cork Examiner disagreed bitterly on tactics. The third daily was the Cork Constitution, with a Unionist and Protestant readership.

As an existing cultural and political institution embedded in the life of Cork, the press occupied a different institutional position to the forms of popular culture in which the earliest manifestations of cinema—Gaudreault’s kine-attractography—were introduced into the city. Nevertheless, the press—along with, and not only as a conduit for, the key institutions of local politics and religion—would be particularly important in defining how cinema would be constituted as an institution in Cork. The local newspapers are also the primary source of information on the integration of cinema into the local community of Cork, but the information they provide offers a far from transparent account of this process. For instance, allowances must be made for the ideological support that Catholic nationalist papers accorded to Catholic Church venues by publishing regular positive notices of them. As well as this, it was a widespread press practice—by no means confined to Cork or even to Ireland—for a newspaper to review positively, and often extensively, the shows at theatres, and later picture houses, that advertised consistently with it. More reliable—but still ideologically encoded by editorial bias and journalistic practice—information must be sought beyond the advertising and review pages, in articles that report on controversies raised by cinema, the efforts of Cork Corporation to regulate the picture houses, and clerical interventions into debates on popular culture.

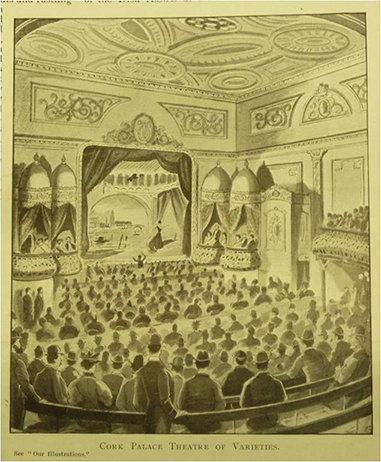

Figure 2: On the left, an artist’s impression of the interior of the Palace Theatre of Varieties prior to its construction (Illustrograph 5:31 (1896): 12); courtesy of the National Library of Ireland. On the right, a plan of the theatre as it appears on Goad’s Insurance Map, 1915; courtesy of Cork City Library.

The “first birth” of cinema in Cork occurred when films were first screened in the city in the 1890s. The earliest screenings were at the Assembly Rooms in April 1896, but a slightly later moment is more revealing (McSweeney 2–3). When Cork’s beautiful new music hall, the Palace Theatre of Varieties, opened on Easter Monday, 19 April 1897, its programme featured Professor Jolly’s cinematograph (“Music Hall” 5). However, it was not the only prominent entertainment with the cinematograph that week: the Speranza charity bazaar also had a cinematograph, but this one did not impress the writer in the Cork Examiner: “The demonstrations not being of the superior character we have been accustomed to witness in the Metropolis, it is little wonder that there was not that amount of acclamation always observable on occasions when material of a superior character has been exhibited” (“Speranza” 6). The first birth of cinema in Cork was a multiple event: in this example, it was not only theatre goers at the Palace who could enjoy a film show but also attendees at the Speranza bazaar. Although the Palace would make a film “act” on its Palascope projector a feature of its programmes in the late 1900s, this did not represent the arrival of cinema as a cultural institution. It was continuing intermediality, in which the film show was still a variety act. The constitution of cinema awaited a second birth.

“What Ails Cork Shows?”

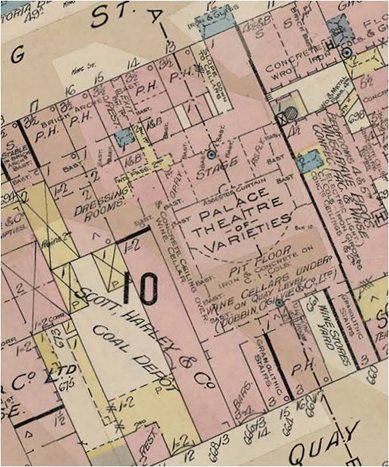

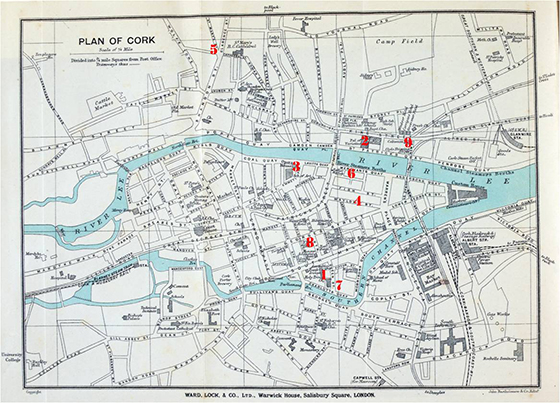

Figure 3: Map of Cork in 1915 showing the locations of the theatres and picture houses between 1910 and 1913. (1) Assembly Rooms, South Mall. (2) Palace Theatre of Varieties, King Street. (3) Opera House, Lavitt’s Quay. (4) Electric Theatre, Maylor Street. (5) St. Mary’s Hall, St. Mary’s Road. (6) Tivoli Picture Theatre, Merchant’s Quay. (7) Fr. Mathew Hall, Queen Street. (8) Imperial Cinema, George’s Street. (9) Coliseum, King Street. Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

An important early moment in the constitution of cinema as an institution in Cork was, paradoxically, the failure of a picture house. The Electric Theatre in Maylor Street—off Patrick Street, the city’s main thoroughfare—opened on Monday, 27 December 1909, making it one of Ireland’s first venues dedicated to film exhibition. This fact already makes the Electric noteworthy, but the public discourse it provoked is particularly important. Rather than its opening as an early dedicated film venue, what made the Electric interesting was the public debate that accompanied its closing. Managed by Allan S. Davenport for Irish Electric Theatres, a subsidiary of a London-based firm, it was initially greeted positively in the press, with the Cork Examiner noting that its inexpensive ticket prices of 2d, 4d and 6d would be a special draw for audiences, while the Cork Constitution described its opening as “an addition to the permanent entertainment halls of Cork” (“Electric Theatre” 7; “The Electric Theatre” 8). A description in the Constitution offered some interesting details of its construction:

One word must be added about the alterations and equipment of the new theatre. This has been done in the short space of eight days entirely by local labour, and an army of fifty workmen has worked practically without a rest day and night, and what a short time ago was a bare warehouse has been literally transformed—as if by the magic of fairy hands—in record time into an up-to-date place of amusement, sparkling with hundreds of electric lights, and capable of accommodating 800 spectators at a time. (“The Electric Theatre” 8)

Although the description of construction as the work of fairy hands is incongruous, the emphasis placed on the fact the labour was sourced locally was an important way in which even proprietors who were not local themselves could stress their reciprocal commitment to the local community through their employment of local manufacturers, contractors and workers.

The Electric advertised in the press and by poster over Christmas and into February 1910, but by the end of February, the Law and Finance Committee of Cork Corporation voted to order its closure, under a power it had recently acquired through the passing of the Cinematograph Act of 1909. The Act primarily introduced provisions for fire safety in picture theatres, a necessity likely to be acknowledged by any reader of the surprisingly frequent reports in the Cork press of fatal cinema fires all over the world. That the Act’s provisions could be used substantially beyond the issue of fire safety was made immediately clear by this case. The debate on the motion to close the Electric Theatre and the subsequent attempts by the company to reopen it are revealing of the conditions for the institutionalisation of cinema in the city. At a corporation meeting on 26 February 1910, by which time the Electric had been in operation for just two months, Councillor Robert Warren moved that the picture house be closed because it showed indecent films, and he was supported by Councillor Denis O’Flynn who held up one of the Electric’s posters that he claimed “was calculated to grossly insult every respectable Catholic in Cork” (“Cork Corporation: Cork Entertainments” 12). Other councillors pointed out that if the Electric Theatre was to be closed on these grounds, then for consistency, they should close other entertainments in the city, including the Opera House about whose production of Can a Woman Be Good? the powerful Catholic Dean of Cork, Michael Shinkwin, had complained in that morning’s newspapers (12; Shinkwin 4). Despite such objections, the Corporation voted to close the Electric. Noting this hostility to popular entertainments in the city, Paddy, the Irish correspondent of the British cinema trade journal Bioscope, asked rhetorically, “what ails Cork shows?” (Paddy 43).

By replacing Davenport with local electrical engineer Cornelius Fielding—who had mounted film shows in the city himself—the company succeeded in persuading the Corporation to allow the Electric to be reopened a couple of weeks later in mid-March, and it ran for another few months before closing permanently. The corporation’s debate on the reopening on 11 March provides further clues as to what councillors thought ailed Cork shows. Although the role of Dean Shinkwin and the deference shown to him by many Catholic councillors had been decisive, other factors contributed to the decision, including the fact that it provided cheap entertainment that could infringe on the business of other entertainment providers and even that it was located in Maylor Street. “[I]t was not to the credit of the citizens of Cork that some of them from time to time went and saw the performances”, commented Sir Edward Fitzgerald, “and that it remained for the clergy to step in and put an end to what they might call an abominable exhibition in an out-of-the-way street, a place entirely unsuited to such performances” (“Cork Corporation: Noisy Scenes” 4). At 2d, the Electric did provide the cheapest advertised entertainment in Cork at this time, undercutting the 3d the Palace charged for entry to its gallery.

Fitzgerald’s objection to location is more difficult to fathom. Maylor Street was no more out of the way in terms of distance from Patrick Street than the prestigious Opera House (Figure 3), but it was a street dominated by warehouses. Perhaps more revealing were the comments of other councillors that show that the Electric had not only contravened the city’s entertainment geography and economics but also that Davenport, as an Englishman, was unacceptable as a manager of this business. The picture house’s solicitor revealed to the Corporation that he had advised the proprietors to appoint a local man, and Councillor Nicholas O’Keeffe lifted his objections “‘now that the place was to be managed by an Irishman, and not by a foreigner’ (hear, hear)” (“Cork Corporation: Noisy Scenes” 4). On Cork’s nationalist dominated Corporation, popular Anglophobia was an acceptable motivation for closing the picture house. Nevertheless, despite Fielding’s appointment, the Electric would not be a success.

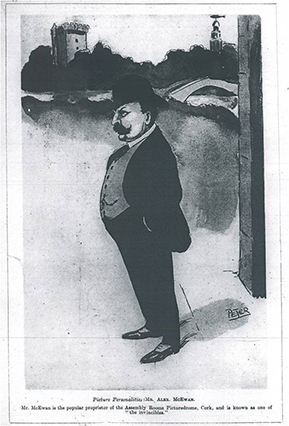

Figure 4: Caricature of Assembly Rooms manager Alex McEwan in a Blarney Castle landscape. The caption reads: “Mr. McEwan is the popular proprietor of the Assembly Rooms Picturedrome, Cork, and is known as one of ‘the invincibles’”. Bioscope 11 Apr. 1912: n.p.

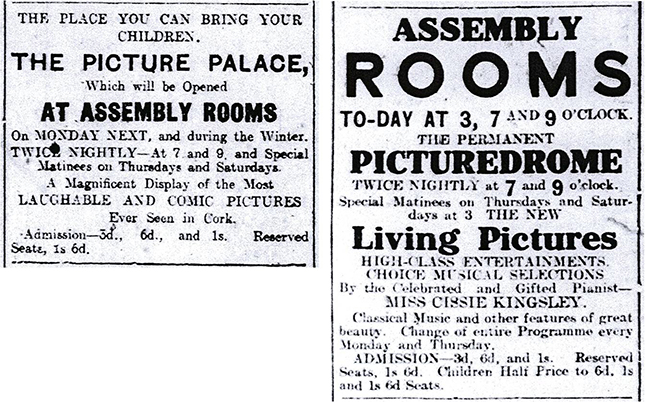

The local conditions that the controversy reveals suggest why the Assembly Rooms Picturedrome on the South Mall—which had operated as a multipurpose meeting hall and entertainment venue since the 1860s—would be Cork’s first successful picture house. Run by a well-known local businessman, Alex McEwan, in a well-established premises, it would over the next two years, from autumn 1910 to autumn 1912, become the most significant dedicated exhibition venue for films in Cork. On 31 October, McEwan reopened the Assembly Rooms for the winter season as the Picture Palace, “the place where you can bring your children”, with two shows nightly at 7 p.m. and 9 p.m. and matinees on Thursdays and Saturdays, and admission prices of 3d, 6d, and 1s (Figure 5, left). By January 1911, McEwan was using the term “Permanent Picturedrome” in advertisements, although the venue was occasionally used for concerts and other events (Figure 5, right). Reviewing the Picturedrome in early January 1911, the Cork Constitution noted that “living pictures as an attraction and amusement seem to grow more and more in public favour” (“Assembly Rooms” 6).

Figure 5: On the left, the Picture Palace at the Assembly Room (Cork Examiner 29 Oct. 1910: 6); courtesy of the Irish Examiner. On the right, the Assembly Rooms Permanent Picturedrome (Cork Constitution 21 Jan. 1911: 4).

The Picturedrome was not the only venue meeting this growing demand for pictures among the Cork public during this period. The Opera House occasionally mounted picture seasons, some of them of several weeks, by such well-known travelling exhibitors as the Irish Animated Picture Company. Developments at the Palace were even more significant, showing how intermediality continued in the variety theatre into the early 1910s. Reopening following refurbishment in December 1908, the Palace added a Palascope slot to its bill in which it exhibited two one- or two-reel fiction films at each show. This element of permanence—even though the films themselves changed—represented an alteration in the way variety programmes of touring acts otherwise operated. As a further elaboration of film’s increasing importance to this variety theatre from 1911 on, more filmed material was added to the programme. Unlike the attention the newspaper reviewers gave to live acts on the variety programme, the Palascope films rarely received comment, except in the case of special films of such topical events as the January 1911 Siege of Sidney Street. “The enterprise exhibited by the management in securing this film so promptly is remarkable,” observed the Evening Echo when the Palace exhibited a film of these events under the title The Battle of Houndsditch, “and no doubt will be amply repaid by well-filled houses” (“Palace Theatre” 2). The success of topical films led the Palace manager Thomas O’Brien to put the Warwick Bioscope Chronicle, a weekly newsreel, on the bill with the usual Palascope films from 17 April 1911. It would soon be replaced by the Pathé Gazette and Gaumont Graphic. As more venues began to show films in 1912, O’Brien followed the programming practices of picture houses—rather than those of the variety theatre—by changing the films shown twice a week, on Mondays and Thursdays. The Palace would become a picture house in the 1930s, but these changes show how evolving cinema industry practices had had an impact on the theatre’s variety theatre bill much earlier.

“Another Smack at the Workingman’s Amusements”

Developments in relation to the Electric, Picturedrome and Palace show that the conditions for the constitution of cinema as an institution in Cork existed from 1910, but the city would not experience cinema’s true second birth until 1912–13. The year between October 1912 and September 1913 saw the openings of five picture houses. Three of these venues opened in late 1912: the St. Mary’s Hall, beside St. Mary’s Catholic Cathedral, at the north-western edge of the city, opened on 21 October 1912; just a month later, the Tivoli Picture Theatre began catering for the taste in pictures of patrons closer to the city centre; and the Fr. Mathew Hall—like St. Mary’s Hall, run by a Catholic Church organisation, the Franciscan Friars—opened in time for the increased leisure time during the Christmas festivities on Queen (now Fr. Mathew) Street, not far from the Assembly Rooms. Just over a month later, on 7 February 1913, the Imperial Cinema opened on George’s (now Oliver Plunkett) Street. Cinemagoers would have to wait seven months for the opening of the Coliseum, the final venue of this period of extraordinary expansion in Cork’s cinema institution.

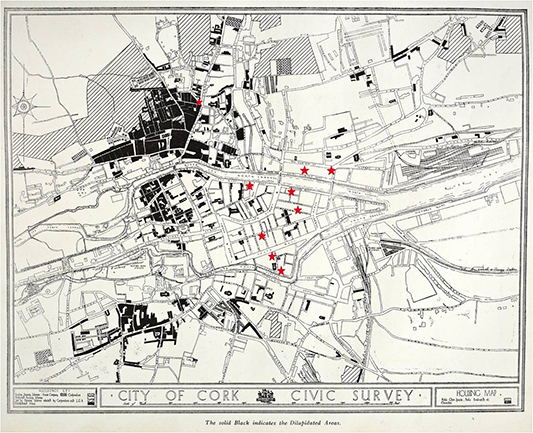

Figure 6: Map showing Cork slums in 1916, with the location of theatres and picture houses marked in red. St. Mary’s Hall (top left) was located at the edge of Cork’s largest slum. (Cork Town Planning Association, plate 9; courtesy of the National Library of Ireland).

The two earliest of these new picture houses—St. Mary’s Hall and the Tivoli—epitomise different aspects of the constitution of cinema by church and commercial picture houses. Given Dean Shinkwin’s opposition, the role of the church-based picture houses appears remarkable, even though Fr. Mathew Hall would exhibit films for just a short period, ceasing screenings in the face of Shinkwin’s onslaught on Sunday film shows in the summer of 1913. The location of St. Mary’s Hall is particularly notable for the way it contravened the city’s existing entertainment geography. This is not just because it was in a mainly residential area outside the commercial core—the wider dispersal of picture houses than other professional entertainment venues was a feature of cinema’s second birth internationally that was also observable in Dublin and Belfast—but because that residential area was on the edge of the city’s largest slum (Figure 6). It was clear in 1917 to Alfred Rahilly, writing about Cork’s poverty, that going to the pictures had become a fact of working-class life that contributed to “secondary poverty”, whereby the working poor who would have just enough to buy life’s necessities further impoverished themselves through ignorant, improvident or idealistic spending: “What should be spent on suitable food or necessary clothes is spent on unnutritious food, on drink, on tobacco, on the picture house, on Church or Trade Union, or on the compulsory, but half unnoticed impost extorted by the State whenever the poor buy tea or sugar” (183). Intended as a temperance institution to attract local residents away from pubs, St. Mary’s Hall had begun five years earlier to make picture going a local amenity for the poor of the North Parish who could afford—or chose to pay for—its 3d or 6d tickets (which were reduced to 2d or 4d in 1913).

The church-sponsored picture houses were crucial in legitimising cinema as a respectable form of recreation, but the cinema institution would increasingly become integrated into the cultural life of the city through more commercial circuits. As a church venue, St. Mary’s Hall could also rely on the fact that the Cork Examiner, Evening Echo and Cork Free Press would publicise its shows without requiring the advertising rates paid by the Opera House, Palace and commercial picture houses. As the ambivalence of the Church’s commitment to cinema became more obvious in the renewed opposition articulated by Shinkwin in the summer of 1913, the task of integrating cinema fell increasingly to the commercial picture houses, which had to seek their own forms of cultural legitimation. Like the Electric before them, they emphasised their embeddedness in Cork by their commitment to the use of local labour in the alteration or construction of premises, a strategy that allowed them to access the hegemonic discourse on encouraging Irish industry. Accounts of the openings of the Tivoli prominently mentioned the fact that the construction work was carried out by the firm of Councillor Daniel Hegarty, and those of the opening of the Coliseum named the many local firms contracted (“New Picturedrome” 7; “Coliseum Theatre, Cork” 6; Figure 1).

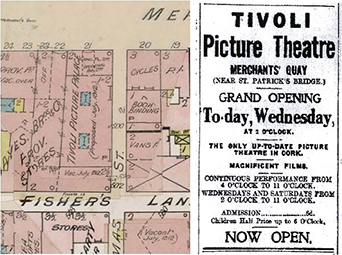

Figure 7: On the left, plan of the Tivoli, at 21 Merchant’s Quay, from Goad’s Insurance Plan of Cork, 1912; courtesy of Cork City Library. On the right, an advertisement announcing the picture theatre’s opening, Cork Free Press 20 Nov. 1912: 4.

On 20 November 1912, when the Tivoli Picture Theatre had opened on Merchant’s Quay, close to Patrick’s Street, all of the newspapers carried an almost identically worded article—clearly prepared by the proprietors—that contended that

[t]he present age is one that is subjected to all manner and modes of taste, and the community, however small, which has no opportunities for cultivating those various tastes is truly at a disadvantage. As in all other features of refinement, there is a taste in pictures—in living pictures above all, and Cork has certainly cultivated that taste to a wonderful degree, when one considers the few opportunities it has had. (“New Picturedrome” 7)

The Tivoli management was anxious to emphasise its progressiveness and cultivated a taste for novelty in cinemagoing by offering its performances “on the continuous plan, such as is being carried out in the leading halls in England and Dublin” that patrons could drop into at any point in the day between 4 p.m. and 11 p.m.—2 p.m. and 11 p.m. on Wednesdays and Saturdays—at a cost of 6d for adults and 3d for children (7). Although dearer than the cheapest seats at the Picturedrome, Palace or St. Mary’s Hall, this single price reflected the design of the building, in which all seating was “of the very latest style, plush covered tip-up seats, firmly secured to the floor” and where the sightlines to the screen—“a specially prepared one, got up on the latest improved style”—were unobstructed by pillars (7). The articles also emphasised the Tivoli’s unique fire-safety features.

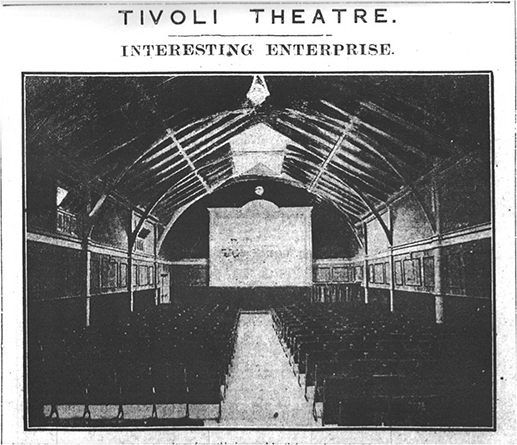

Figure 8: Photograph of the interior of the recently opened Tivoli. Cork Examiner 23Nov. 1912: 10; courtesy of the Irish Examiner.

Despite stressing these progressive elements, the Tivoli management—followed in due course by the proprietors of the Imperial and Coliseum—was also careful to indicate the picture house’s contribution to the local community. The proprietors’ claims that not only were they local themselves but that they also supported local labour were indirectly but very publicly supported by Thomas Murray, the representative of the furnishing trades on the city’s Trades’ Council, who entered into a correspondence with Alex McEwan in the Evening Echo in the first half of November 1912 over the refurbishment of the seating in the Picturedrome. “If the Tivoli Theatre promoters are satisfied, after inquiries from English manufacturers, to give the contract to a local firm,” Murray argued, “it should be, in my view, worth of emulation by Mr. McEwan, to whom it would be very insignificant indeed when taken in connection with the bountiful harvest he has been reaping from the patronage of the working people of Cork” (4).

Murray’s comments and St. Mary’s Hall’s location and pricing point to a Cork picture-house audience that was substantially working class. Although it is difficult to discuss audiences in terms that go beyond indicating that the growth in picture houses could only have taken place on the basis of substantial popular support, the controversy over Sunday opening in the summer of 1913 provides evidence that members of the Cork public were willing to defend this form of entertainment. This period was marked by the increasing efforts of the Catholic Church and the corporation to assert control over what had clearly become a highly popular entertainment. The Church was in a contradictory position. On the one hand, the provision of film entertainment by the St. Mary’s and the Fr. Mathew Halls was one further and particularly successful way for these temperance institutions to occupy a large group of people with a popular activity that did not involve the consumption of alcohol. On the other hand, the picture house was a new and barely regulated social space offering relatively cheap and accessible amusement produced almost entirely abroad and, as such, potentially offering the moving-picture equivalent of the salacious literature that the church-based Vigilance Committees had recently been formed to eradicate. Although the Catholic Church prided itself on not being as strictly Sabbatarian as some of the Protestant Churches, such an influential cleric as Dean Shinkwin, who had a suspicion of popular entertainments in general and, it seemed, picture houses in particular, was unlikely to be convinced that going to the pictures was a suitable Sunday activity. Neither of the church venues mounted film shows on Sundays (Corkery 2; Long 3), but the Tivoli and the Imperial did exhibit on Sundays and were unwilling to give up easily what they argued to be their most lucrative day of the week.

Therefore, when on 11 June 1913, the five members of the corporation’s Law and Finance Committee unanimously voted to make renewal of the cinematograph licences before them conditional on Sunday closing—once again on the promptings of Shinkwin (“Cinema Halls in Cork: The Question of Sunday Opening” 3)—controversy seemed inevitable (“Cork Cinema Theatres” 3). What was surprising and novel was that the first responses came from correspondents to the newspapers defending Sunday performances. One of the earliest letter writers was J. O’Brien who noted the lack of justification of the measure by the five members of the committee “who apparently consider themselves entitled to direct the tastes and amusements of a population of nearly a hundred thousand people (including the suburbs), and embracing all shades of social life” (3). “Corkonian” pointed out that the “City Fathers, perhaps, have their hotels, clubs, etc., to go to on a wet Sunday. What! The temptations for the public on a wet Sunday, only the publichouse” (5). These written responses seem not to have been the only way the councillors experienced the displeasure of picture-house patrons. At the meeting of the corporation on 27 June to ratify the decision of the committee, Councillor William Fleming, who had presided at the committee, defended its decision but complained that “those who had agreed to the recommendation were regarded as ‘Puritans,’ ‘killjoys,’ etc.” (“Cork Corporation: Election of City Coroner” 4). Therefore, it was under considerable popular pressure that the corporation decided to send the matter back for reconsideration to the committee, who in turn invited clergy and representatives of the picture houses to give their views at a special meeting on 15 July.

Although certain features of the controversy on Sunday opening reprised the events of the closing of the Electric three years previously, some significant developments show that cinema had become a cultural institution in the city. These were not evident at the committee meeting, where many councillors displayed a remarkable deference to Dean Shinkwin, epitomised by chairman Jeremiah Lane’s assurance “that anything the rev. gentleman would request them in all reason and fairness the committee would be most anxious to comply with, knowing as they did that he had the best interests of his fellow citizens at heart” (“Cinema Halls in Cork: Sunday Opening Question” 6). In such a context, the outcome appeared inevitable, and Shinkwin took full advantage of the committee’s invitation to address them first by speaking at length. He assured them that not only he but all Catholic clergy in Cork were opposed to any Sunday shows, and he highlighted the particular dangers for young people of love stories “when pictorial art is set to work and brings out with completeness and striking force the inordinate affection and unchaste tendency that breathe through the story” (6). Indeed, as in the Electric case, Shinkwin’s views would prevail, when the committee unanimously confirmed its recommendation that an undertaking to remain closed on Sundays should be a condition of cinematograph licences. At a more fractious meeting on 25 July—and following another letter to the councillors from Shinkwin—the corporation ratified the committee’s decision (“Cork Corporation: Increased Railway Rates” 3).

Cinema became a cultural institution in Cork not because it could assert itself in defiance of the church and local politics but because it could adapt itself to the operations of such powerful local institutions. By 1913, Cork had acquired and was indulging a taste for pictures to such an extent that cinema’s institutional birth had occurred. The pictures as a cheap form of entertainment made the picture house a feature of the streetscape and a place where working-class people could enjoy entertainment and sociability in a way not possible before the 1910s, even if the nature of that sociability is little evident in surviving sources. Nevertheless, the Sunday opening controversy offers some glimpses of Cork’s early cinema audiences. Reflecting on the controversy in a letter to the Evening Echo, F. W. Pillow described the ban of Sunday opening as “over-zealous legislation” that represented “another smack at the workingman’s amusements” (3). “Every time ministers of any denomination interfere with the amusements of the people,” he warned, “the working man’s mind turns towards Socialism, and, if he seldom says anything, he still thinks and waits his time, and his time is coming fast” (3).

References

1. “Assembly Rooms”. Cork Constitution 10 Jan. 1911: 6. Print.

2. Battle of Houndsditch. Andrews’ Pictures, 1911. Film.

3. Bunny Blarneyed. Dir. Larry Trimble. Vitagraph, 1913. Film.

4. Census of Ireland 1901/1911. The National Archives of Ireland. Dec. 2007. Web. 15 July 2013.

5. “Cinemas”. Evening Echo 7 July 1913: 2. Print.

6. “Cinema Halls in Cork: Sunday Opening Question”. Evening Echo 15 July 1913: 6. Print.

7. “Cinema Halls in Cork: The Question of Sunday Opening”. Evening Echo 9 July 1913: 3. Print.

8. “Coliseum Theatre, Cork”. Evening Echo 2 Sep. 1913: 6. Print.

9. Condon, Denis. “A Century of ‘Cinematographing Ireland’”. History Ireland 18.6 (Nov/Dec 2010): 38–9. Print.

10. “Cork Corporation: Agenda for Friday’s Meeting”. Cork Free Press 7 Nov. 1912: 7. Print.

11. “Cork Corporation: Cork Entertainments”. Cork Examiner 26 Feb. 1910: 12. Print.

12. “Cork Corporation: Increased Railway Rates”. Evening Echo 25 July 1913: 3. Print.

13. “Cork Corporation: Noisy Scenes”. Evening Echo 11 Mar. 1910: 4. Print.

14. Corkery, John F. “Letter to the Editor: Cork Cinema Theatres”. Evening Echo 12 June 1913: 2. Print.

15. Corkonian. “Letter to the Editor: Cinema Performances”. Evening Echo 14 June 1913: 5. Print.

16. Cork Town Planning Association. Cork: A Civic Survey. Liverpool: U.P. of Liverpool; and London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1926. Print.

17. “Current Literature: Reviews of Recent Publications”. Freeman’s Journal 23 Dec. 1913: 2. Print.

18. “Electric Theatre”. Cork Examiner 27 Dec. 1909: 7. Print.

19. “The Electric Theatre”. Cork Constitution 27 Dec. 1909: 8. Print.

20. Gaudreault, André, and Philippe Marion. “A Medium Is Always Born Twice...” Early Popular Visual Culture 3.1 (2005): 3–15. Print.

21. Gaudreault, André. “The Diversity of Cinematographic Connections in the Intermedial Context of the Turn of the 20th Century. Visual Delights: Essays on the Popular and Projected Image in the 19th Century. Eds. Simon Popple and Vanessa Toulmin, Trowbridge: Flicks Books, 2000. 8–15. Print.

22. ---. “From ‘Primitive Cinema’ to ‘Kine-Attractography’”. The Cinema of Attractions Reloaded. Ed. Wanda Strauven. Amsterdam: Amsterdam U.P., 2006. 85–104. Print.

23. Goad, Charles E. Insurance Plan of Cork. Maps. Cork City Council, nd. Web. 26 June 1913.

24. Government of Ireland. Decade of Centenaries. All Party Oireachtas Consultation Group on National Commemoration, nd. Web. 9 July 2013.

25. Long, J. F. “Letters to the Editor: Cinema Performances”. Evening Echo 12 June 1913: 3. Print.

26. Maltby, Richard, and Melvyn Stokes. “Introduction”. Going to the Movies: Hollywood and the Social Experience of Cinema. Eds. Richard Maltby, Melvyn Stokes and Robert C. Allen. Exeter: U. Exeter P., 2007. 1–22. Print.

27. Maltby, Richard. “New Cinema Histories”. Explorations in New Cinema History: Approaches and Case Studies. Eds. Richard Maltby, Daniel Biltereyst and Philippe Meers. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011. 3–40. Print.

28. McSweeney, John. The Golden Age of Cork Cinemas. Cork: Rose Arch, 2003. Print.

29. Murray, Thomas. “Letter to the Editor: Trades Council and Mr McEwan”. Evening Echo 7 Nov. 1912: 4. Print.

30. “The Music Hall: Brilliant Opening Night”. Cork Examiner 20 Apr. 1897: 5. Print.

31. “The New Picturedrome”. Cork Free Press 23 Nov. 1912: 7. Print.

32. O’Brien, J. “Letter to the Editor: Cinema Performances”. Evening Echo 13 Jun 1913: 3. Print.

33. O’Hanlon, Terence. “Picture Houses: Big Boom in Bioscopes”. Irish Independent 23 Dec. 1913: 4. Print.

34. The O’Kalem Collection. Dir. Peter Flynn. Irish Film Institute/BIFF, 2010. DVD

35. Paddy. “What Ails Cork Shows?” Bioscope 10 Mar. 1910: 43. Print.

36. “Palace Theatre”. Evening Echo 10 Jan. 1911: 2. Print.

37. Pillow, F. W. “Letter to the Editor”. Evening Echo 27 July 1913: 3. Print.

38. Rahilly, Alfred J. “The Social Problem in Cork”. Studies 6 (1917): 177–88.

39. Rockett, Kevin, with Emer Rockett. Film Exhibition and Distribution in Ireland, 1909–2010. Dublin: Four Courts, 2011. Print.

40. Shinkwin, Michael. “Letters to the Editor”. Cork Examiner 26 Feb. 1910: 4. Print.

41. “Speranza: Opened Yesterday: The Numerous Attractions”. Cork Examiner 20 Apr. 1897: 6. Print.

42. Stack, Eilis. “Victorian Cork”. Cork: Historical Perspectives. Ed. Henry Alan Jefferies. Dublin: Four Courts, 2004. Print.

Suggested Citation

Condon, D. (2013) '''A taste in pictures": the second birth of cinema in Cork', Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 6, pp. 5–22. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.6.01.

Denis Condon lectures on film at the School of English, Media and Theatre Studies, National University of Ireland Maynooth. His research interest lies in the area of early cinema, and his publications on this subject include the book Early Irish Cinema, 1895–1921 (2008), and articles in such journals as Early Popular Visual Culture, Screening the Past and Field Day Review.